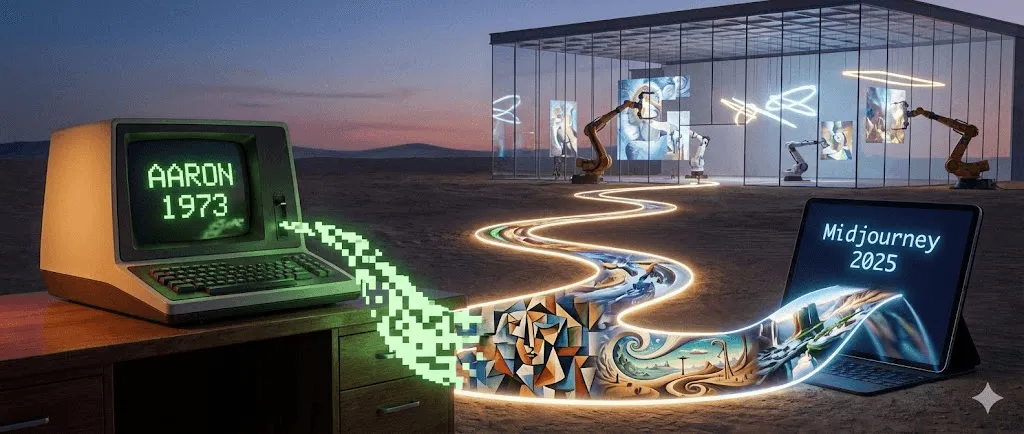

The Complete History of AI Art: From AARON to Midjourney (1973–2025)

Last Updated: 2026-01-22 18:07:34

How artificial intelligence transformed from academic curiosity to artistic revolution and why it matters

This guide walks through AI art history from early rule based systems to today’s diffusion models so you can see how each breakthrough changed what artists could do.

When a Robot Sold Art for Nearly Half a Million Dollars

In October 2018, something unprecedented happened at Christie's auction house in New York. A portrait somewhat blurry, vaguely reminiscent of 18th century European painting sold for $432,500. The buyer? An anonymous collector. The seller? French collective Obvious. The artist? An algorithm.

"Portrait of Edmond de Belamy" wasn't painted by human hands. It was generated by a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) trained on 15,000 historical portraits. The signature in the corner wasn't a name but a mathematical formula: "min max Ex[log(D(x))] + Ez[log(1 D(G(z)))]."

The art world was divided. Some called it a watershed moment. Others called it a gimmick, even a scandal, especially when it emerged that the collective had used open source code without proper attribution to the original programmer, Robbie Barrat. But regardless of the controversy, one thing became clear: AI-generated art had arrived, and there was no putting this particular genie back in the bottle.

But here's what most people don't realize: that 2018 auction wasn't the beginning of the history of AI art. It wasn't even close. The story actually starts 45 years earlier, in a university computer lab, with a British painter who decided his paintbrush wasn't challenging enough anymore.

Quick Timeline:

1960s: Early computer/algorithmic art experiments lay the groundwork

1973: Harold Cohen starts AARON

2015: DeepDream + early style transfer go viral

2014–2018: GANs push image realism; AI art enters galleries/auctions

2021: CLIP unlocks text image understanding

2022: Diffusion models + Midjourney / DALL·E / Stable Diffusion mainstream AI art

2023–2025: Copyright, dataset consent, provenance tools, regulation debates intensify

The Accidental Pioneer: How a Painter Created the First AI Artist

Harold Cohen and AARON (1973–2016)

In 1968, Harold Cohen was at the top of his game. He'd represented Britain at the Venice Biennale. His abstract paintings hung in respected galleries. But something was nagging at him. As he later recalled, "Maybe there are more interesting things going on outside my studio than inside it."

Cohen was teaching at UC San Diego when he encountered computers. Not as a tool for digitizing his existing work, but as something more fundamental could a computer itself create art? Not reproduce, not copy, but genuinely create?

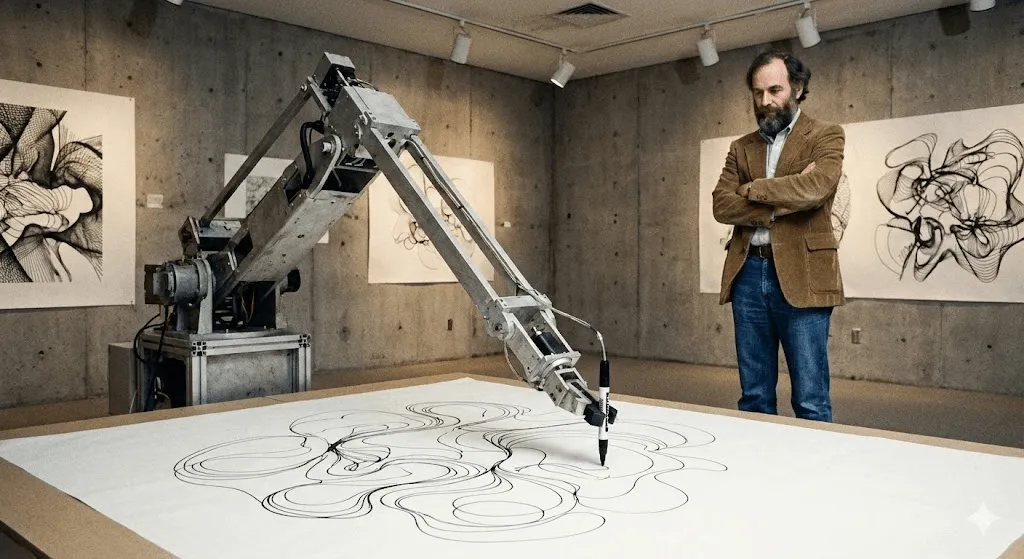

The result was AARON, named partly after Moses' brother in Exodus. When Cohen first demonstrated it at UC Berkeley in 1974, AARON could only generate abstract patterns. But here's what made it revolutionary: it didn't just execute predetermined instructions. Cohen had programmed it with rules about composition, closure, and form concepts he understood as a painter but within those rules, AARON made its own decisions.

Think of it like this: Cohen taught AARON the grammar of visual language, but AARON wrote its own sentences.

By the 1980s, AARON was creating recognizable imagery human figures, plants, interior scenes. Cohen would set it loose with a robotic drawing arm (built with collaborators in university research environments, as Cohen explored how code could “draw” in the physical world), and it would produce intricate drawings. Each one unique. Each one unmistakably AARON's style, but each one different.

What's fascinating is that Cohen could never fully predict what AARON would create. He found that some of his programming instructions generated forms he hadn't imagined. The machine was showing him possibilities within his own artistic system that he hadn't seen.

AARON continued evolving for over 40 years. The 2001 version generated colorful scenes of figures and plants. The 2007 version ("Gijon") created jungle-like landscapes. When Cohen died in 2016, he left behind not just thousands of artworks, but a profound question: if AARON surprised its creator with novel compositions, was it creative?

Major institutions including the Whitney have exhibited Cohen’s AARON related work and documentation, underscoring its importance in digital art history. You can still see AARON's work generating images today, though anything created after Cohen's death is considered controversially inauthentic.

Before AARON: Generative Art and Early Computer Experiments (1960s)

Long before today’s models, artists were already using algorithms to generate visual forms. Early computer plotter drawings and rule based “generative art” in the 1960s introduced a core idea that still defines AI art: the artist designs a system, and the system produces variations beyond manual repetition.

The Quiet Decades: AI Art Before the Hype (1980s–2000s)

While Cohen worked on AARON, other artists were exploring computational creativity, though few people outside academic circles noticed.

Karl Sims might be the closest thing to a household name from this era, at least in digital art circles. Working at MIT Media Lab in the 1980s and later at Thinking Machines (a supercomputer company), Sims created 3D animations using "artificial evolution." His process: generate random 3D forms, let them mutate, select the interesting ones, repeat. It's basically natural selection for digital creatures.

His 1991 piece "Panspermia" and 1992's "Liquid Selves" won top prizes at Ars Electronica, the prestigious digital arts festival. If you've seen those hypnotic, organic looking 3D animations that don't quite look like anything in nature but feel oddly alive Sims pioneered that aesthetic.

Scott Draves took a different approach with "Electric Sheep" (1999). It's a screensaver yes, remember those? but one that learns. Distributed across thousands of computers, it generates evolving fractal animations called "sheep." When viewers vote on which patterns they like, the system breeds more of those patterns. It's still running today, actually. Go to electricsheep.org and you can watch it.

During this period, the term "generative art" became common. Artists were writing code that set rules and parameters, then letting algorithms create within those constraints. Processing, a programming language designed specifically for artists, launched in 2001 and made this more accessible.

But here's the thing: none of this felt like "AI" to most people. These were cool digital art projects, sure, but they didn't seem intelligent. They didn't understand what they were making. They were following rules, however complex.

That was about to change.

Deep Learning Changes Everything (2012–2015)

Something fundamental shifted in the early 2010s. Three things converged:

First, GPUs (graphics processing units) got powerful enough to train massive neural networks. Ironically, chips designed for gaming enabled AI breakthroughs.

Second, big datasets became available. ImageNet, launched in 2009, contains millions of labeled images. Suddenly, neural networks had enough examples to actually learn patterns.

Third, deep learning algorithms improved dramatically. In 2012, deep learning models dramatically improved image recognition benchmarks (popularized by ImageNet), signaling that neural networks could learn visual patterns at scale., crushing traditional computer vision approaches. Researchers realized: if you make neural networks deep enough (many layers), give them enough data, and enough computing power, they start doing things that look surprisingly intelligent.

For art, the implications were profound.

The Deep Dream Moment (2015)

In June 2015, Google engineer Alexander Mordvintsev published something weird. He'd been working on visualizing how neural networks recognize objects. The idea: if a network is trained to recognize dogs, what happens if you reverse the process and ask it to enhance whatever dog like patterns it sees in an image?

The results were trippy. Psychedelic. Hallucinogenic, even. Feed it a photo of clouds, and the network would see dog faces, eyes, and architectural elements everywhere, then amplify them into surreal landscapes. The artistic community went wild.

Google called it DeepDream (officially "Inceptionism"). Within weeks, artists were creating galleries of DeepDream art. It became its own aesthetic that particular style of images covered in eyes and swirling organic patterns. Even today, you instantly recognize a DeepDream image.

What made it culturally significant wasn't just the visuals. It was the realization: this is what a neural network sees when it looks at the world. It's not seeing what we see. It's seeing patterns, correlations, statistical relationships. And those patterns, when visualized, look like fever dreams.

It was deeply weird. And people loved it.

Style Transfer: Neural Networks as Artists (2015–2016)

Around the same time, researchers figured out how to use neural networks for "style transfer", taking the style of one image and applying it to another. Want to see your photo rendered in the style of Van Gogh's "Starry Night"? Done in seconds.

The technical paper was dense (Gatys et al., 2015), but apps implementing it proliferated. Prisma became a viral hit in 2016. Suddenly, anyone with a smartphone could make "art" that looked like famous paintings.

Critics pointed out this wasn't really creating new art it was algorithmic mimicry. But it showed that neural networks could understand artistic style well enough to replicate it. That was new.

GANs: The Technology That Broke Through (2014–2020)

For artists, GANs mattered because they made “style” learnable from data so you could explore a visual universe without hand coding every rule.

How GANs Work (Without the Math)

In 2014, Ian Goodfellow then a PhD student at the University of Montreal introduced Generative Adversarial Networks in a paper that would become one of the most cited in machine learning. Yann LeCun, a founding father of deep learning, called GANs "the most interesting idea in machine learning in the last 10 years."

Here's the concept: imagine two neural networks playing a game against each other.

Network 1 (the Generator): Tries to create fake images that look real.

Network 2 (the Discriminator): Tries to tell fake images from real ones.

The Generator starts terrible creating random noise. The Discriminator easily spots fakes. But here's the clever part: the Generator learns from its failures. It adjusts to fool the Discriminator. The Discriminator gets better at spotting fakes. The Generator adjusts again. Back and forth, thousands of times.

Eventually, the Generator gets so good that even the Discriminator can't reliably tell fake from real. At that point, you have a neural network that can generate convincing images from scratch.

The breakthrough: GANs don't need human labeled training data for every possible output. They learn the underlying statistical distribution of whatever they're trained on faces, landscapes, anything and can generate infinite variations.

From Weird Faces to Convincing Art (2015–2018)

Early GAN results were... let's say "experimental." If you remember those nightmare fuel AI generated faces from around 2015 distorted, uncanny valley nightmares, those were early GANs. Researchers shared them as proof of concept, and they promptly became memes.

But the technology improved fast. By 2017, NVIDIA's Progressive GAN could generate 1024×1024 faces indistinguishable from photographs. In 2018, their StyleGAN pushed resolution even higher and added control over different aspects of images.

Artists started experimenting. Mario Klingemann, a German artist, created "Memories of Passersby I" (2018) an installation featuring two screens showing endlessly generated portraits. They scroll past like memories, never repeating. It sold at Sotheby's for £40,000.

Helena Sarin took a different approach: training GANs on her own drawings rather than photographs. This let her maintain artistic control while leveraging AI's generative power. Her "AI Candy Store" series has a distinctive aesthetic recognizably AI, but with her personal style baked in.

Robbie Barrat, then a high school student, trained GANs in classical art and shared his code openly on GitHub. (This is the code that Obvious would later use for Christie's sale, sparking controversy about attribution and artistic credit.)

The Next Rembrandt (2016)

Before Obvious's auction splash, there was "The Next Rembrandt" (2016) a marketing project by ING bank and several Dutch institutions. They scanned Rembrandt's 346 paintings, trained an algorithm to understand his style, and generated a "new" Rembrandt portrait.

It wasn't technically a GAN, but the concept was similar: can AI create in a specific artist's style? The project got massive media coverage. Critics called it a technical achievement but questioned whether it was art or merely sophisticated pastiche.

It raised questions we're still wrestling with: Is training on a specific artist's work respectful homage or computational appropriation? When does inspiration become theft?

The Explosion: When AI Art Went Mainstream (2022–Present)

CLIP: Teaching AI to Understand Text and Images (2021)

The next breakthrough came from OpenAI in January 2021: CLIP (Contrastive Language Image Pre training). The technical details are complex, but the impact was simple: CLIP could understand the relationship between text and images.

Previous systems required labeled data: "this is a cat," "this is a dog." CLIP learned from 400 million image text pairs scraped from the internet. It learned that certain words tend to appear with certain visual features. This created a shared "space" where text and images could be compared.

Why this mattered: combine CLIP with a generative model, and suddenly you can generate images from text descriptions. Type "an astronaut riding a horse," and the system knows what that should look like.

Artists quickly hacked CLIP into their workflows. Combining it with GANs or other generators, they could guide image creation with language. It was clunky, but it worked.

The 2022 Revolution: DALL E 2, Midjourney, Stable Diffusion

Then came 2022, and everything changed at once.

DALL E 2 (OpenAI, April 2022) combined CLIP with diffusion models (more on those in a moment) to generate high quality, coherent images from text. Early access went to selected artists and researchers. The waitlist ballooned over a million people. The images OpenAI shared were stunningly creative, coherent, often beautiful.

Midjourney (Midjourney Inc., July 2022) took a different approach: community driven, Discord based, focused on aesthetic beauty. It quickly developed a distinctive look painterly, dramatic, often fantastical. Artists flocked to it. The Discord server became one of the most active creative communities online.

Stable Diffusion (Stability AI, August 2022) was the game changer for accessibility. Unlike DALL E 2 (web only, controlled access) or Midjourney (subscription based), Stable Diffusion was open source. Anyone could download it, run it locally, modify it.

Within months, an entire ecosystem sprouted: web interfaces, mobile apps, plugins for Photoshop, hundreds of customized models trained for specific styles. The explosion was unprecedented.

By late 2022, social media was flooded with AI art. "Prompt engineering" became a skill. People shared tips for getting better results. Arguments erupted constantly about whether this was democratizing art or destroying it.

Diffusion Models: The Tech Behind the Magic

So what's a diffusion model? It's actually inspired by physics specifically, how particles diffuse through a medium.

The training process:

- Take a real image

- Gradually add noise to it until it's pure random static (forward diffusion)

- Train a neural network to reverse this process remove noise (reverse diffusion)

The generation process: Start with pure noise, run the reverse diffusion process, end up with a coherent image. Text conditioning (via CLIP) guides what kind of image emerges.

Why diffusion models beat GANs for this application: they're more stable, easier to train, and better at following text prompts. GANs are still used for some things, but diffusion models dominated the 2022 explosion.

Technical aside: The key paper was "Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models" (Ho et al., 2020), though earlier work by Sohl Dickstein et al. (2015) laid groundwork. If you want to really understand this stuff, those papers are starting points, but be warned heavy math ahead.

The Numbers

- By early 2023, these tools had reached millions of users, and AI images began saturating social platforms.

- DALL E: 3+ million users (waitlist cleared)

- Stable Diffusion: Impossible to count (open source, distributed), but GitHub stats suggest millions

People generated hundreds of millions of AI images. Entire businesses sprouted offering AI art services. Stock photo sites scrambled to figure out policies. Traditional artists watched in dismay as "AI artist" became a job title.

The Other AI Art: Academic Applications

While everyone focused on text to image generators, researchers were quietly using AI to revolutionize art historical scholarship. This part of AI art history gets less attention, but it's arguably more academically significant.

Computer Vision for Attribution and Analysis

Art historians have always struggled with attribution determining who created a specific work. Now neural networks are helping.

Rutgers Art & AI Lab (led by Ahmed Elgammal) developed systems that analyze brushstrokes, compositional elements, and stylistic markers to identify artists or detect forgeries. In 2017, they correctly identified the artists of unlabeled works with over 90% accuracy in controlled tests.

Reconstruction of Lost Works: Neural networks trained on an artist's known works can generate plausible reconstructions of lost or damaged pieces. The most famous example: using AI to extrapolate Rembrandt's "The Night Watch," damaged in 1715, showing what the cut off portions might have looked like. (Though art historians debate accuracy, it's informed speculation, not recovery.)

Herculaneum Scrolls: In 2023, computer scientists used machine learning to read text from ancient scrolls carbonized by Vesuvius in 79 AD. The scrolls are too fragile to unroll, but CT scans plus trained neural networks could detect ink patterns. This is AI enabling us to read ancient texts for the first time in 2000 years. (Source: Nature, 2023)

Museums and AI

Major institutions have experimented with AI in fascinating ways:

The Met has experimented with AI driven collection visualization mapping large scale museum archives into a “latent space” to surface unexpected relationships across objects.: Collaboration between the Metropolitan Museum, MIT, and artist Refik Anadol. They trained neural networks on the Met's entire collection (375,000+ artworks), then visualized the "latent space" the conceptual territory between different types of objects. It revealed unexpected connections: an ancient Persian ewer and a 19th century vase might be conceptually close in ways human curators never noticed.

MoMA's AI experiments: Refik Anadol's "Unsupervised" (2022–2023) used machine learning trained on MoMA's collection to generate flowing, dreamlike projections in the museum's lobby. Art purists were divided, some saw it as gimmicky, others as a new way to experience museum archives.

LMU Munich's Transparent AI Project: Led by Professor Hubertus Kohle, this research develops AI tools for art history that explain their reasoning. Normal neural networks are "black boxes" . You get an answer but don't know why. This project makes AI decisions transparent, crucial for scholarly acceptance. They're training models to identify visual similarities between artworks and explain what features drove their conclusions.

These applications don't generate new art, but they're changing how we study art history. That's arguably more lasting than any generated image.

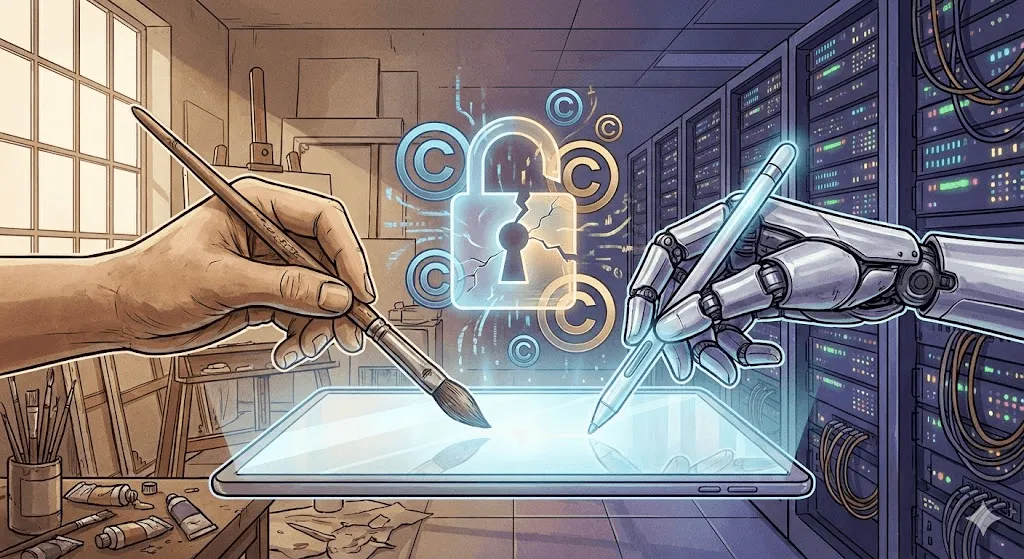

The Controversy: Copyright, Ethics, and the Future of Creativity

This is where things get heated. The technical achievements are impressive, but the ethical implications are... complicated.

The Copyright Battle

The core issue: AI art models are trained on billions of images scraped from the internet. Many are copyrighted. Artists weren't asked permission. They weren't compensated. And now systems trained on their work can generate images "in their style" within seconds.

Major lawsuits filed:

Getty Images vs. Stability AI (January 2023): Getty alleges Stability scraped millions of their images for Stable Diffusion training. They have evidence that some generated images include partial Getty watermarks, visibly showing their source.

Class action by artists vs. Midjourney, Stable Diffusion, DeviantArt (January 2023): Led by artists Sarah Andersen, Kelly McKernan, and Karla Ortiz. Alleges massive copyright infringement. The case is ongoing as of late 2024, and legal experts are divided on likely outcomes.

The legal question: Is training on copyrighted images fair use (like a student learning by studying existing art), or is it infringement (using work without permission for commercial gain)?

Courts haven't decided yet. The answer will shape the entire industry.

Artist Responses: Fighting Back

Artists aren't waiting for courts. They're developing technical countermeasures.

Glaze (University of Chicago, 2023): Software that subtly alters digital artwork in ways invisible to humans but that "poison" AI training. If a model trains on Glazed images, its outputs become distorted. It's like an active watermark that corrupts rather than identifies.

Nightshade (also U of Chicago, 2023): More aggressive than Glaze. Doesn't just protect the Nightshaded image, it actively degrades the model's overall performance. Upload enough Nightshaded images labeled "dog" that actually show cats, and eventually the model becomes confused about what dogs look like.

These tools are controversial. AI researchers call them harmful sabotage. Artists call them self defense. Both have points.

The "Do Not Train" proposal: Artists and advocates have proposed metadata tags marking work as off limits for AI training. Some platforms (DeviantArt, Shutterstock) implemented opt out systems. But enforcement is minimal. AI companies can simply ignore the tags, and many do.

The Creativity Debate

Deeper than copyright is a philosophical question: Is AI generated art actually art?

Arguments it isn't:

- Lacks human intentionality and emotional depth

- Generated by recombining existing work, not creating something truly novel

- Requires no skill anyone can type a prompt

- Undermines what makes art valuable: human creativity and struggle

Arguments it is:

- Tools don't make art less valid (cameras didn't end painting)

- Prompt engineering and curation are skills

- Humans guide the AI, making creative decisions

- Enables new forms of expression impossible before

My take: This is the wrong debate. It's like arguing whether photography is art in 1850. Of course AI can create art we've seen it. The better questions are: What kind of relationships do we want between human and machine creativity? Who benefits? What gets lost? What gets gained?

The Job Displacement Reality

This isn't theoretical. Real people are losing work.

A 2023 survey by the Concept Art Association found:

- 73% of concept artists reported reduced job opportunities

- 62% had lost freelance gigs to AI

- Entry level positions disappearing most rapidly

Companies are using AI for preliminary concept work, storyboards, background designs exactly the work that used to go to early career artists. Some defenders argue this is no different than digital tools replacing traditional techniques. But the pace is unprecedented, and the affected artists are understandably angry.

On the other hand, new roles are emerging: AI art directors, prompt engineers, specialists in AI human hybrid workflows. Whether these will replace lost jobs at a 1:1 ratio remains to be seen.

The Bias Problem

AI art models inherit biases from their training data. Ask for "a CEO" and you get white men. "A nurse" gives you women. "A beautiful person" heavily skews toward young, white, conventionally attractive faces.

Google's Gemini tried to correct this in 2024 by increasing diversity in historical images and overcorrected badly, sparking controversy over how models balance historical accuracy, representation, and safety. The incident highlighted how hard it is to tune these systems responsibly and racially diverse 1700s European nobility. Google apologized and took the feature offline. The incident showed how hard it is to balance historical accuracy with representation.

Bias isn't just about demographics. AI art tends toward certain aesthetics polished, commercial, conventionally pretty. Experimental, avant garde, deliberately ugly art is rarer in outputs because it's rarer (and less rewarded) in training data. AI, in this sense, can be artistically conservative even when technically radical.

Where We Are Now (2024–2025)

The Current Landscape

As of late 2024/early 2025, the AI art space has matured but remains turbulent:

DALL E 3 (integrated with ChatGPT Plus) improved prompt interpretation dramatically. You can now have conversations about what you want, and the AI understands nuance better.

Midjourney V6 pushed aesthetic quality even higher, with better text rendering (still not perfect) and more controllable styles.

Stable Diffusion XL and beyond continues evolving, with the open source community creating specialized models for everything from anime to photorealism to specific artistic styles.

Adobe Firefly represents the "responsible AI" approach trained only on Adobe Stock images and public domain content, with commercial licensing built in. It's less capable than Stable Diffusion but legally safer for commercial use.

Video Generation: The Next Frontier

Text to image was just the beginning. 2024 saw serious progress in AI video generation:

Runway Gen 2 and Pika can generate short video clips from text or images. Quality remains uneven objects morph unnaturally, physics gets weird but improves monthly.

OpenAI's Sora (announced February 2024, limited release) demonstrated photorealistic, coherent video up to a minute long. The demo videos were jaw dropping. They also scared a lot of people that deepfakes were already a problem before AI could generate convincing video from text.

3D and Beyond

AI art is expanding beyond 2D images:

Point E and Shap E (OpenAI) generate 3D models from text prompts. Quality is still limited, but the trajectory is clear.

NeRF (Neural Radiance Fields) technology can generate 3D scenes from 2D images, with implications for everything from filmmaking to game development to architectural visualization.

Music, Text, and Multimodality

AI music generation (Suno, Udio) reached "pretty good" status in 2024. AI hasn't replaced musicians, but it's making functional background music easier and cheaper to produce.

Multimodal models (GPT 4 with vision, Gemini) can analyze images, generate text about them, then generate new images based on that text. The boundaries between text AI and image AI are blurring.

What's Next: Predictions and Possibilities

Near Term (2025–2027)

Likely:

- Video generation reaches mainstream usability

- Consistent character generation (same person across multiple images) becomes reliable

- More legal clarity on copyright (forced by ongoing lawsuits)

- Industry consolidation as smaller players get acquired or shut down

- Backlash intensifies, with some platforms/clients banning AI art

Possible:

- Real time video generation during video calls or streaming

- AI art becomes standard tool in professional creative workflows

- Emergence of "certified human made" art as premium category

- Major museum exhibition of AI art history (beyond single installations)

Medium Term (2027–2030)

Speculative but plausible:

- Text, image, video, 3D, and audio generation unified in single models

- Personalized AI models trained on individual artistic styles become common

- AR/VR integration enables AI art in physical spaces through headsets

- Legal frameworks establish (likely messy) compromises on training data

- New artistic movements emerge that are native to AI, not adaptations of pre AI styles

Long Term: The Big Questions

Will AI surpass human creativity? Wrong question they're different things.

Will human artists become obsolete? Unlikely. Demand for "authentically human" work may actually increase as AI floods the market with easy content.

Who owns AI generated art? Still being fought in courts. Current US copyright law says nobody owns it (no human authorship), but that will change.

How do we compensate artists whose work trains AI? This is the billion dollar question, literally. Possible solutions: licensing fees, per use micropayments, compulsory licensing systems like music. None exist yet at scale.

Should there be AI free zones? Some argue certain applications (children's books, memorials, legal evidence) should be reserved for human creators. Others call this Luddism. Debate ongoing.

Lessons from History

Looking back over 50+ years of AI art history, a few patterns emerge:

- The tools get democratized. AARON required programming expertise. GANs require machine learning knowledge. Modern tools require a Discord account. Each generation is more accessible.

- Initial hype exceeds reality. Every breakthrough prompts "art is dead" proclamations. Art doesn't die. It adapts.

- Legal and ethical frameworks lag behind technology. We're still debating copyright questions from technologies deployed three years ago. Law moves slowly; technology doesn't.

- Concerns about displacement are often justified but incomplete. Yes, some jobs disappear. But new ones emerge. The transition period is painful, especially for those caught in it.

- Art survives. Photography didn't kill painting. Digital tools didn't kill traditional media. AI won't kill human creativity. But it will change how, why, and what we create.

Conclusion: Writing the Next Chapter

From Harold Cohen's patient programming in 1973 to millions generating images in seconds today, the history of AI art is ultimately a story about changing relationships between human creativity and computational capability.

The questions facing us now aren't primarily technical the technology works, and it's improving rapidly. They're human questions:

- How do we ensure AI amplifies rather than replaces human creativity?

- How do we fairly compensate artists whose work makes AI possible?

- Who gets to participate in this new creative landscape?

- What parts of creativity do we want to keep uniquely human?

- How do we preserve artistic careers and livelihoods during technological transition?

These questions don't have easy answers. They require negotiation between artists, technologists, companies, policymakers, and the public. The history of AI art isn't finished we're living through one of its most consequential chapters right now.

What's certain is that ignoring AI won't make it go away, and neither will pretending it doesn't raise real challenges. The path forward requires engagement: honest about problems, open to possibilities, insistent on fairness.

As for whether AI can truly be creative maybe we're asking the wrong question. Creativity isn't a binary property that you either have or don't. It exists on spectrums, in collaborations, in unexpected combinations. If AI art's first 50 years have taught us anything, it's that creativity is more expansive and stranger than we thought. And humans, for better or worse, seem determined to share it.

The next chapter is being written now. Contribute thoughtfully.